What is applied science fiction?

The form of applied science fiction that I work on involves scientists and technologists bringing their expertise to the process of my writing, to create stories that are based on the science and technology they are working on.

This is a 90 second explanation of applied science fiction for the Robot Talk Podcast

In the video below, Christine Aicardi from King’s College London and I are interviewed by Luke Robert Mason from the Futures Podcast about our collaborations in applied science fiction.

This was as part of the launch of my collection Extracting Humanity which includes seven stories from these applied science fiction projects.

Reading the applied science fiction stories in public with the cutting edge researchers present, creates a bridge between them and the general public.

These events give both expert and non-expert a chance to step back from their subjective views and discuss the ethical issues of where this science and technology might take us.

The beauty of using stories in this way is that these potential futures can be seen and discussed through the eyes of a third-party i.e. the characters in the story.

“If I would choose one thing that [participating in the project] may have affected, it was my willingness to disseminate our science and our results to the public; I’m more prone to that. I enjoy it more. But I also think it’s more important.” Scientist participant.

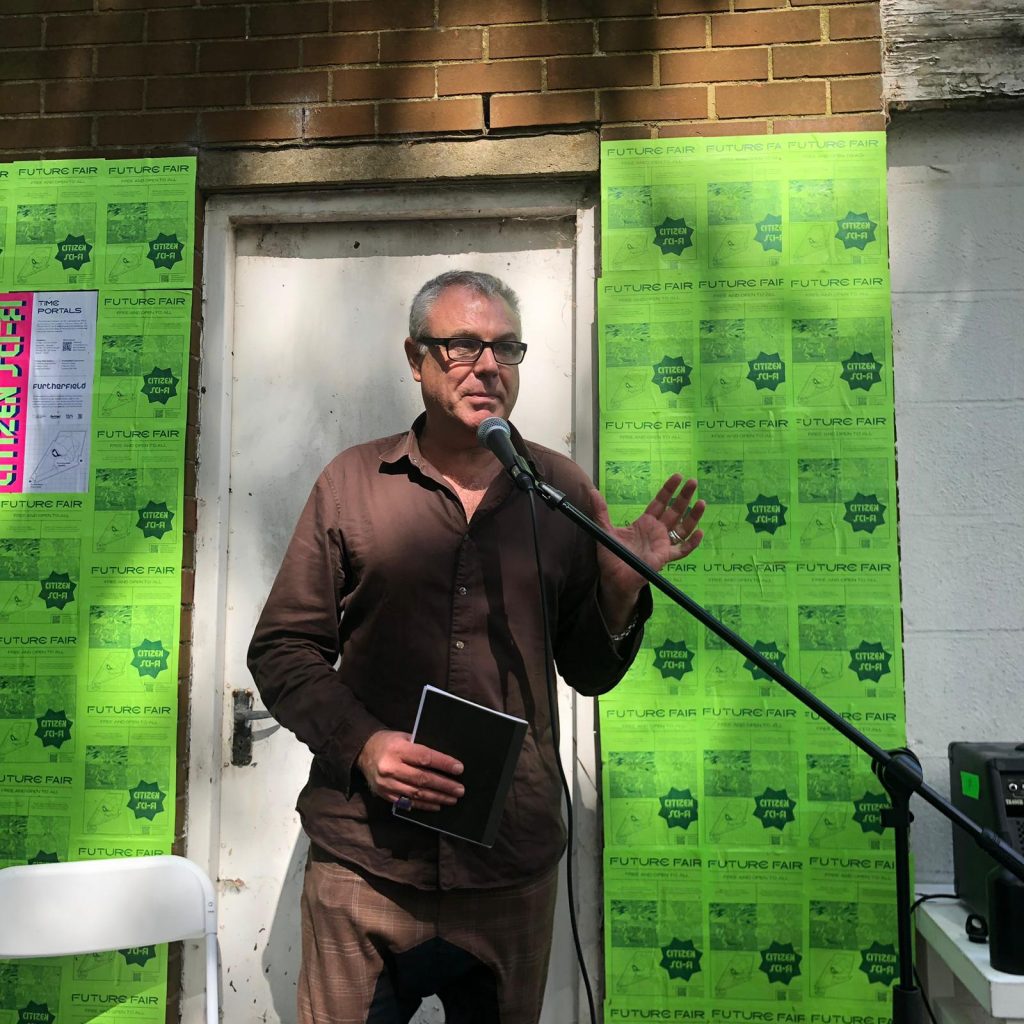

“Stephen Oram worked in a number of highly engaging ways to encourage residents to imagine future worlds with him. In particular his live reading at our [Furtherfield] Future Fair captivated audiences where he read a section of the story and then hosted a discussion with attendees. Oram’s work was the perfect fit and we look forward to collaborating again. ” Dr. Charlotte Frost, Executive Director, Furtherfield.

“There is a public out there hungry for forums where they can explore the complex shades of ethical grey surrounding science and innovation.” Dr Christine Aicardi, King’s College London

If you are interested in taking part in projects as a writer, scientist, technologist etc. then please join the discord server for Applied Science Fiction.

There’s a list of where you can find the stories here.

These are my current projects:

Fitzrovia Futures 2055

A locally run project to facilitate a discussion between subject specialists in areas that will affect the future and the local community on those possible futures for Fitzrovia. Through workshops and storytelling, the project will use participatory foresight and applied science fiction to create a ‘level playing field’ for all involved, to explore what’s possible and what’s preferable for Fitzrovia in the 2050s. [read more]

These are some of my most recent projects:

- An 18 month project with the think tank Cybersalon, working with speculative authors and specialists in: Police & Justice; Power & Energy; Finance & Digital Money; Health & Longevity; and Learning & Education. Ideas about possible futures of each were discussed, iterated and written about through short stories and commentary on the ideas in those stories. The output was All Tomorrow’s Futures: Fictions That Disrupt

- A project with King’s College London which is, “piloting development of an automated approach to coding expressed emotion in mothers’ speech to improve prediction of youth mental health problems.” The result will be two pieces of fiction that contribute to the ethical discussions about this use of this technology. These have been used in public engagement events with more to come.

- The Creative Futures project with Coventry University and the Defence Science and Technology Lab, to identify and examine the challenges of the future through a series of discussion events between science fiction writers and DSTL researchers.

Update: The report and associated fiction should be published soon. - Flüsterfutures – future of homes. A project with Anhalt University of Applied Sciences where imaginings of future homes are ‘whispered’ from one phase of the project to the next. I’ll be writing three pieces of flash fiction, based on workshops discussing artefacts created for the project.

- Mirror Machine: a writing challenge for 15 to 18 year olds, exploring the future of digital twins – this is with King’s College London and the Digital Twin Hub. [Here are some supplementary materials]

Background

I’ve been working on science fiction projects with scientists and future tech folk since 2016 and intend to carry on for as long as they’ll have me.

First of all it’s worth saying that I realise science fiction inspired by emerging science is nothing new. In fact it could be argued that Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein because of what she learned about the science of Galvani, Volta and Aldini via her father’s friends Humphry Davy and William Nicholson who were the era’s leading electrical researchers.

However, I’ve not come across many examples where the scientist and the science fiction author share a stage in front of an audience to read the stories and answer questions. Which is what I’ve been doing.

The purpose of this page is to give a bit of background to the projects I’ve been working on; if you’re interested in finding out more or working with me on similar projects please get in touch .

About the projects

I write near-future science fiction, taking emerging science and technology and placing it in a speculative world. A world where it’s ubiquitous, but imperfect at interacting with us pesky irrational and messy humans.

So how does near-future fiction and emerging science and technology come together in these projects?

Firstly, for the purposes of good science fiction it’s vital to get a true albeit lay-person understanding of the science rather than relying on news stories, which can be alarmist and even wrong.

Secondly, collaboration gives me the opportunity to push the limits of the possible and the plausible in the knowledge that the experts I’m working with can validate it. That’s not to say that the stories that come from these projects are utopian and evangelistic for the science. Hardly any of them are, but they do try to paint a possible future. Although often with elements we would wish to avoid.

Striking the right balance between being overly positive and overly negative is a careful call because the apocalyptic sucks out any energy for hope and being naively positive ignores the problems we need to solve. Either extreme makes the story less useful for exploring possible futures.

The great thing about these projects is that they produce work that sits in that grey area between utopia and dystopia. This is partly because that’s where I like to place my stories and partly because through the process of working together, the scientists and by implication the science are humanised rather than demonised which in turn reduces the tendency of near-future fiction to be entirely dystopian. It’s also interesting how much the scientist’s personalities influence the fiction.

Often the project ends with us sharing a stage at a public event, which brings an added sense of responsibility.

In all of the projects where there is a public engagement aspect, the scientists have a right to veto the science in a story. Not the story itself, but the accuracy of the predicted technology or science. This is particularly important if we are to share a stage and be nice to each other.

Before I give an overview of how the projects tend to run, it’s worth mentioning some of the labs I’ve been working with.

The first lab I visited in 2016 was the Bristol Robotics Lab, as part of a project with the European Human Brain Project.

After a day spent at the lab, we three writers produced short pieces which were reviewed for plausibility by the scientists and then revised before being read at the Bristol Literary Festival as part of a panel with the scientists. I was also part of a panel presenting the work of this project at the Science in Public 2017 conference.

My story from this project was Eating Robots.

Because the Bristol Robotics Lab were so welcoming and engaging, they made me want to do more.

In 2018, I worked with the Department of Developmental Neurobiology and the Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London as part of the Strange Brains, Alien Minds project. This involved two days of visits, a few weeks of story creation and editing in collaboration with the scientists and culminated in two events sponsored by King’s Cultural Institute and again by the Human Brain Project.

The first of these was an internal event for King’s College London of two panels to stimulate discussion. One was comprised of scientists from the participating labs and the second brought perspectives from history, philosophy and the social sciences.

The second event was open to the public and was a sell out. At Waterstones on Tottenham Court Road in London the authors from the project plus Jennifer Rohn and Ken MacLeod who both have plenty of experience in collaborating with scientists read the stories and discussed working with scientists.

My story from this project was Zygosity Saves the Day.

In 2019, I worked on another fascinating project – Future Fictions of Finsbury Park – which was part of the Furtherfield Citizens SciFi project to celebrate 150 years of the park by considering its future. This involved leading a day long workshop with scientists from a broad range of disciplines (architecture, smart cities and urban mental health to mention a few) and residents of Finsbury Park. We discussed the emerging science and technology and how that might affect the future of the park and its surrounding area. As a result we built a world in which to base my short fictional story.

This was then read to an audience in the park followed by a session digging into what of this future world the audience wanted. For example, which of the characters they’d prefer to be – the resident of the park with their hand-to-mouth existence, the rich ship-dweller with mental health issues, or the highly skilled refugee looking for a home. We also touched on their appetite for bioengineered plants and bioengineered humans.

My story from this project was Long Live the Strawberries of Finsbury Park, which was subsequently published as an augmented reality zine and then selected for the Best of British Science Fiction 2022 anthology by Newcon Press.

In my collections of short stories I have included responses from the scientists I have worked with and to give you a small sample here’s an excerpt from Professor Alan Winfield of the Bristol Robotics Lab and Dr Claire Steves from Twins UK.

“The problem with personhood is that it confers rights and responsibilities, but if an AI is to be held responsible for its actions there must be some way of applying sanctions when it causes harm. How to come up with a meaningful punishment for an AI is by no means obvious, but Stephen’s anxiety loop offers a thought-provoking future possibility.” Alan Winfield, Professor of Robot Ethics, UWE.

“I think the title of this moving piece should really be Compassion saves the day. Human compassion – from one person, Lara, to another, Beatrice. Their love enables them to beat the system. Sadly, the frightening future medical system in which they live is far from compassionate: removing freedom from the old and infirm, and passing judgement on individuals because of their past choices. The story shows how even apparently beneficial endeavours – such as understanding how to help an individual remain healthy into old age – can be misused if we are not careful.” Claire Steves, Clinical academic Deputy Director of TwinsUK and Consultant Geriatrician at Guys and St Thomas’s hospital.

The projects have all been fascinating and have given me the opportunity to see behind the scenes and to get paid to research and write science fiction. I recognise that with this privilege comes responsibility and one of those responsibilities is to make sure that as far as possible the projects have a long lasting impact. That’s where Dr Christine Aicardi comes in.

She is a senior researcher in science and technology studies in the Foresight Lab of the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at King’s College London, has been a fulltime collaborator of the Ethics and Society subproject of the Human Brain Project since 2014, and the driving force behind the projects with KCL. As a key element of the projects she has interviewed the scientists, the writers and surveyed the audiences about their experiences and how they have been influenced and affected by the process and the stories.

Based on this research she very kindly agreed to write the foreword to my second collection, Biohacked & Begging, in which she says: “[…] it seems that the most ethically engaged scientists and seasoned public engagement actors can discover new ways of thinking thanks to their encounter with near-future fiction.”

She also says in the foreword that: “[…] one such scientist told me that although he had always been an avid science fiction reader, inspired and influenced by it, this had been mostly far future hard sci fi; but his collaboration with us got him interested into near-future fiction, which he was reading a lot more since, and he thought the best of it was especially good for bringing out deep sociological perspectives. He added, it had also triggered the realisation that what they were doing in his lab was turning fiction into facts, was realising what had hitherto been only imagined: for him, the best stories are thought experiments, and as a scientist there is a responsibility in the choice of which imagined future to help turn into fact.”

Another important insight she has shared with me is that, “for historians of science, the science fiction of an era is a precious source of primary material, which can shed additional light on the complex, historically and geographically situated, relations between science, technology and society.”

I owe a great deal to Christine, especially in expanding my experience of how to get the best out of these collaborations.

As I mentioned at the top of this page, I’m keen to do more of these types of projects and to continue to learn how they can contribute to a strong and positive future.

As I’ve often said, “The future is ours and it’s up for grabs…”

Please contact me if you want to discuss a project or have an idea we can work on together.

Images:

photo credit: Robotics and Autonomous Systems Showcase 2023 (keynote)

photo credit: Rusty Russ Twisted Tree ReTwisted via photopin(license)

photo credit: mclcbooks Roots via photopin(license)

photo credit: corno.fulgur75 13e Biennale de Lyon: La Vie Moderne 2015 via photopin(license)