I was struck recently by a piece in Nature: the international journal of science on what science fiction has to offer a world where technology and power structures are rapidly changing.

As the headline says, “With technological change cranked up to warp speed and day-to-day life smacking of dystopia, where does science fiction go? Has mainstream fiction taken up the baton?”

It’s a fairly widely held view that sci-fi doesn’t predict the future very well, but it’s good at helping us think about on our own humanity in a changing world and some of the articles reflect on this.

We might be rubbish at predicting the future because technology doesn’t develop in a straight line, but many of the scientists I’ve spoken to will tell you about the sci-fi that inspired them. Although, I guess that’s influencing rather than predicting.

Something that I didn’t pick up in the articles that I think is important is whether we would be so sensitive to real-life ‘dystopia’ if we hadn’t had hugely popular sci-fi such as Nineteen Eighty Four, Brave New World, Blade Runner and more recently Black Mirror.

Have these works of science fiction made us more attuned to the attempts to manipulate us, or more wary of how technology might go wrong once you mix the messiness of humanity with the cracks in the code?

I think they have, I think they give us cautionary tools.

Whatever your view on science fiction these six articles by leading sci-fi writers are well worth a read.

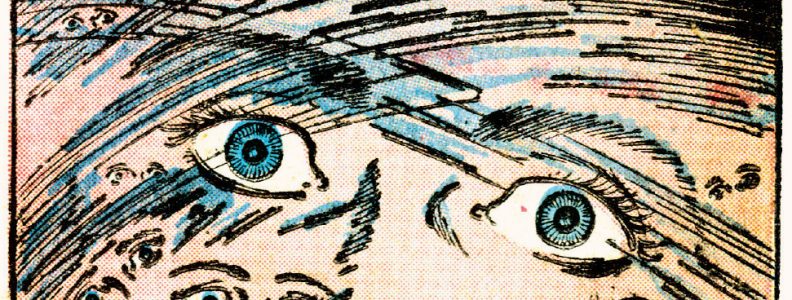

photo credit: creative heroes The Supervision – Stop Mass Surveillance! via photopin (license)