As part of the 2017 Fitzrovia Festival, the people live here festival, neural scientists, social scientists, science writers and science fiction authors all came together to take an audience on their different journeys of collaboration.

Georgina Ferry and Kathrin Jacobsen introduced Neural Architects, the behind-the-scenes account of a unique collaboration between a leading architectural practice, Ian Ritchie Architects Ltd, and a community of scientists seeking to understand how we think, feel, understand and remember. The outcome of this collaboration was the evening’s host building, the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre.

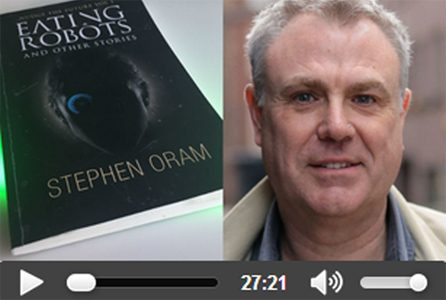

I read from my new collection, Eating Robots and Other Stories, including The Thrown Away Things – a tale of interconnected and dangerously discarded ‘things’ – and the title story Eating Robots about an errant old lady and her errant robot.

Christine Aicardi (Senior Research Fellow, King’s College London) has been a key person in my collaborations with the Bristol Robotics Laboratory and the Human Brain Project. She read her own short fiction, Tablet Stroker, and made many insightful observations about The Thrown Away Things and suggestions on what to look out for as we head off into the future. You can read her thoughts in the back of the collection.

Swimming with the Algorithms was a piece I wrote especially for the evening. The idea came out of a series of conversations with Danbee Kim (Researcher at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre and Scientist-in-Residence at the Brighton Sea Life Centre). The piece was iterated over a series of exhanges between me and Danbee touching on both the believability of the science and the behaviour of the protaganist. On the night I read the story and Danbee gave her thoughts on it and what it was like to collaborate on its creation.

There were questions throughout from the audience ranging from: ‘Do Asimov’s three robot laws help or hinder in the writing of fiction about robots?’; ‘What is the most scary thing about present day technology?’; and ‘What’s the best thing about collaborating?’

The conversations continued for at least an hour and a half after the formal part of the evening; the discussions I was involved in were fascinating, whether about the art of writing or the meaning of intelligence.

A big thank you to the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for being such good hosts.

photo – left to right: Christine Aicardi, Danbee Kim, Kathrin Jacobsen, Georgina Ferry and Stephen Oram